Public Economics

Chile pension reform modeling: methodology, assumptions, and results

Context and motivation

This article summarizes modeling work developed at Chile’s Budget Directorate (Dipres) by a technical team during the initial proposals of the pension reform. The final law introduced relevant changes (e.g., parameter adjustments and implementation schedule) while keeping actuarial sustainability criteria. The architecture and sensitivity planning were led by management; the applied programming was executed by the analysis team. The goal was to quantify, from an actuarial perspective, the reform’s effects on the non‑contributory pillar (PGU) and the contributory pillar, including the Social Security Insurance (SSP) and the Integrated Pension Fund (FIP).

Model architecture

A microsimulation model with transition matrices by sex, age and income is used. Each person transitions yearly between states (not affiliated, affiliated, contributor, non‑contributor, retiree, deceased), enabling long‑horizon projections of contribution density, balances, retirement age and pension modality. With these trajectories we compute benefits and system flows over a horizon long enough to reflect demographic transition and system maturity.

Flow equations (sketch)

- Contributions: mandatory contributions to individual accounts and the additional rate that funds the SSP, subject to cap and participation/formality rates.

- Accumulation: capitalization with expected real returns, fees and changes by pension modality.

- Benefits: PGU plus contributory and complementary SSP benefits, with eligibility and calculation rules tied to work history.

- FIP: revenues from contributions and returns; expenses from SSP benefits and admin costs; financing rules and long‑term investment policy.

Data and assumptions

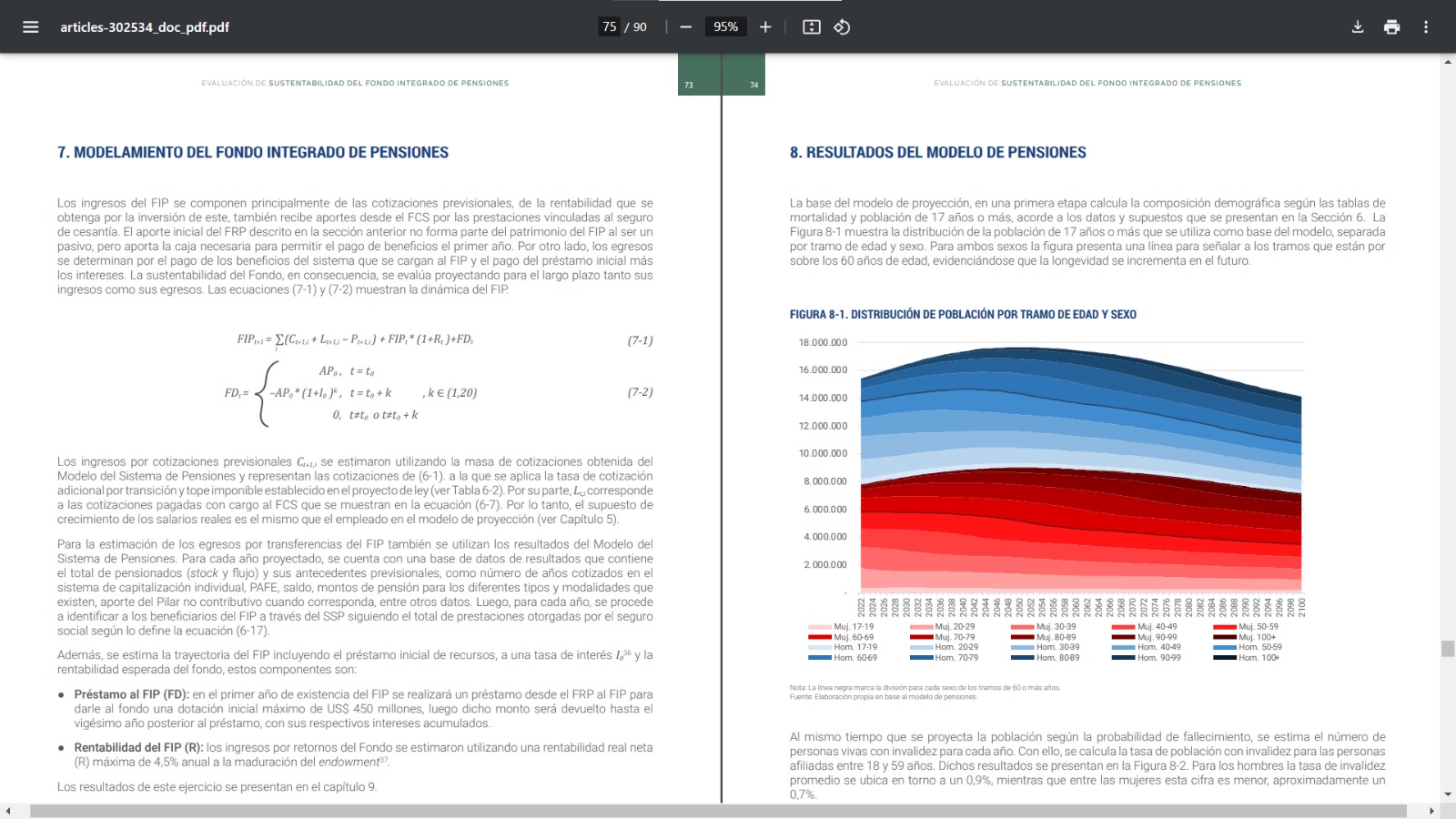

- Demographics: age/sex projections with longevity trajectory aligned with the horizon.

- Labor market: participation, formality and contribution density by cohorts and income percentiles, capturing gaps.

- Finance: long‑term real returns, fee structure and investment policy consistent with an extended horizon.

- System rules: institutional parameters (PGU, caps, pension modalities, eligibility) and implementation timelines.

Modeled reform components

Non‑contributory pillar (PGU)

Coverage and amounts increase, interacting with self‑financed pensions and eligibility thresholds, affecting replacement rates across deciles.

Contributory pillar and Social Security Insurance (SSP)

The additional 6% contribution funds the SSP through the FIP. For analytical clarity we separate components:

- Intragenerational solidarity savings: complements self‑financed pensions conditional on months contributed.

- Intergenerational guarantee: ensures a minimum when the calculated pension is below a threshold tied to work history.

- Gaps complement: focuses resources on interrupted trajectories.

- Maternity complement: recognizes periods associated with childcare.

- Caregivers complement: compensates interruptions due to caregiving.

FIP modeling

The FIP is treated as a long‑term fund with a diversified portfolio including less liquid assets. Short‑term performance may show a J‑curve; in the long run a positive real return with low correlation to traditional assets is targeted. Each period we evaluate revenues (contributions and returns), expenses (SSP benefits and costs), accumulated balance and sustainability metrics under stress scenarios.

Main results

- SSP coverage: gradual increase as the system matures and new cohorts retire under the reformed scheme.

- Pension amounts: the intragenerational component boosts low pensions with sufficient contribution density; the intergenerational guarantee protects weaker trajectories.

- FIP sustainability: consistent path to finance projected benefits under the reference scenario; sensitivity analyses delineate risk ranges.

Validation and sensitivity

Calibration reproduces observed aggregates (affiliation, density, contributions, pensions) and distributions by age, sex and income. Sensitivities include macro‑financial (real return, CPI), labor (formal employment, wages) and demographic (longevity).

Challenges and lessons

- Data quality: reconciliation between admin sources and surveys; treatment of gaps and reporting lags.

- Heterogeneity: high dispersion in individual trajectories requiring fine segmentation and consistent thresholds.

- Horizon: long windows and conservative assumptions, with periodic parameter reviews.

- Communication: decomposing effects by component improves interpretation and avoids misattribution.

Technical document

The full technical report with methodology, detailed assumptions, diagrams and extended results is available here.

View document (PDF)

Keywords

actuarial model, microsimulation, transition matrices, Social Security Insurance, Integrated Pension Fund, PGU, sustainability, ageing, contribution density, real return rate, Chile